Uzbekistan Travel Guide

In terms of sights alone, Uzbekistan is Central Asia’s biggest draw and most impressive showstopper

The heart of Central Asia and the historic hub of the region. The most settled of all the states, it’s home to the romantic-sounding cities of Samarkand and Bukhara. Like the rest of the region, much of its beauty lies in its friendly people. Go off the beaten track and there’s much to explore, from a Soviet avant-garde art museum in the west to the palaces of the last Khan of Kokand in the east. With the mildest climate of all the ‘stans, it’s best visited between February and October.

Fast navigation

Destination Highlights

SAMARKAND

Samarkand (Marakanda to the Greeks), one of Central Asia’s oldest settlements, was probably founded in the 5th century BC. It was already the cosmopolitan, walled capital of the Sogdian empire when it was taken in 329 BC by Alexander the Great, who said, ‘Everything I have heard about Marakanda is true, except that it’s more beautiful than I ever imagined.’

A key Silk Road city, it sat on the crossroads leading to China, India and Persia, bringing in trade and artisans. From the 6th to the 13th century it grew into a city more populous than it is today, changing hands every couple of centuries – Western Turks, Arabs, Persian Samanids, Karakhanids, Seljuq Turks, Mongolian Karakitay and Khorezmshah have all ruled here – before being obliterated by Chinggis Khan in 1220.

Registan Square

In the 14th – 15th centuries, the Registan was not only a trade and crafts square but was also the cultural center of the city. In 1417-1420 Ulugbeg erected his madrassah on this square. In the 17th century, the ruler of Samarkand, Yalangtush Bakhadur, made up his mind to reconstruct the square. He ordered to erect of the Sher-Dor madrassah (1619-1636) and subsequently the Tilla-Kari Madrassah (1646-1660). Thus, the completed ensemble still astonishes with the harmony and uniqueness of any madrassah ever created.

Shakhi-Zinda

Shakhi-Zinda Necropolis is famous for its beauty of mausoleums, tiled with turquoise and blue mosaics.

It was established with a single religious monument over 1,000 years ago. Various temples, mausoleums, and buildings were continually added throughout the ensuing centuries, from approximately the 11th century to the 19th. The result is a fascinating cross-reference of various architectural styles, methods, and decorative craftsmanship as they have changed throughout a millennium of work.

Gur-Emir Mausoleum

The mausoleum was built for the beloved grandson of Timur. Later Timur himself was buried here in 1405. The building is splendid both inside and out with a majestic blue dome twined with plaits that especially astonish the imagination.

Bibi-Khanim Mosque

The principal city mosque of Bibi-Khanim is a distinguished architectural structure and the largest mosque in Central Asia. The construction of the mosque took place in 1399 after the Indian campaign of Timur, which lasted for five years. It was a splendid and richly decorated structure.

Ulugbek’s Observatory

The remains of Ulugbek’s Observatory is one of the great archaeological finds of the 20th century. Ulugbek was probably more famous as an astronomer than as a ruler. His 30m astrolabe, designed to observe star positions, was part of a three-story observatory he built in the 1420s. All that remains now is the instrument’s curved track, unearthed in 1908. The small on-site museum has some miniatures depicting Ulugbek and a few old ceramics and other artefacts unearthed in Afrosiab.

Afrosiab Museum

The Afrosiab Museum was built around one of Samarkand’s more important archaeological finds, a chipped 7th-century fresco of the Sogdian King Varkhouman receiving ranks of foreign dignitaries astride ranks of elephants, camels, and horses. You’ll see reproductions of this iconic fresco throughout the country. It was only discovered in 1965 during the construction of Tashkent Street. The 2nd floor of the museum leads the visitor on a chronological tour of the 11 layers of civilization that is Afrosiab.

Meros Silk Paper Mill

Located about 10 km from Samarqand on the picturesque banks of the River Siab, the Meros Silk Paper Factory is a family-run unit that has been in operation for about 12 years. Technology for making silk paper came to Samarqand via the Great Silk Road from China around the 7th or 8th century CE. The original silk paper was made from silk fibres, but today it is made from the bark of mulberry trees — the very trees that feed silkworms from whose cocoons silk is extracted.

Oriental bazaar Siab

From ancient times, an oriental bazaar simultaneously performed the functions of a modern-day supermarket and shop. One could find here all possible entertainment, exchange currency, and do many other things. One can purchase anything here: fruits, vegetables, the meat of any kind, and all sorts of dried fruits and crafts, which are placed in their own separate rows. Together with eastern sweets one can buy traditional Samarkand bread that has made Samarkand famous throughout the world.

BUKHARA

Central Asia’s holiest city, Bukhara has buildings spanning a thousand years of history, and a thoroughly lived-in old center that hasn’t changed too much in two centuries. It is one of the best places in Central Asia for a glimpse of pre-Russian Turkestan. Most of the center is an architectural preserve, full of madrassas, minarets, a massive royal fortress, and the remnants of a once-vast market complex.

Try to allow time to lose yourself in the old town, where you may discover 140 protected buildings and many workshops and trade domes.

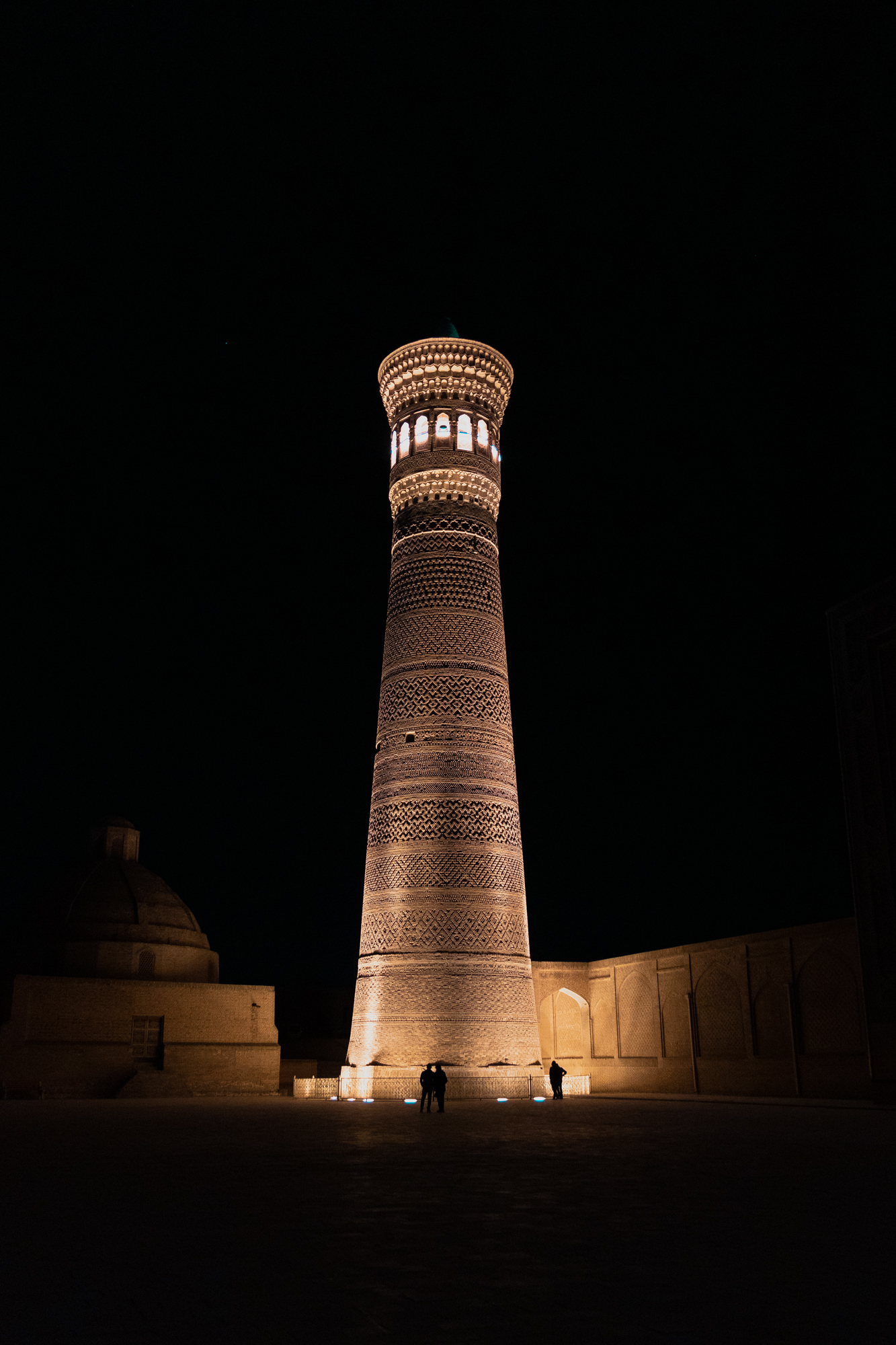

Poi-Kalon Complex

The complex is located in the historic part of the city. Since 713, several ensembles of main mosques were built in this area, to the south of the Ark citadel. One of these complexes, burned down by Genghis Khan during the siege of Bukhara, was built in 1121 by the Karakhanid ruler Arslan-khan. The Kalan minaret is the only one of the structures of the Arslan-han complex that was kept safe during that siege. The minaret is the most famed part of the complex, which dominates the historical center of the city in the form of a huge vertical pillar.

The Ark Citadel

The Ark of Bukhara is a massive fortress located in the city of Bukhara, Uzbekistan that was initially built and occupied around the 5th century AD. In addition to being a military structure, the Ark encompassed what was essentially a town that, during much of the fortress’ history, was inhabited by the various royal courts that held sway over the region surrounding Bukhara. The Ark was used as a fortress until it fell to Russia in 1920. Currently, the Ark is a tourist attraction and houses museums covering its history.

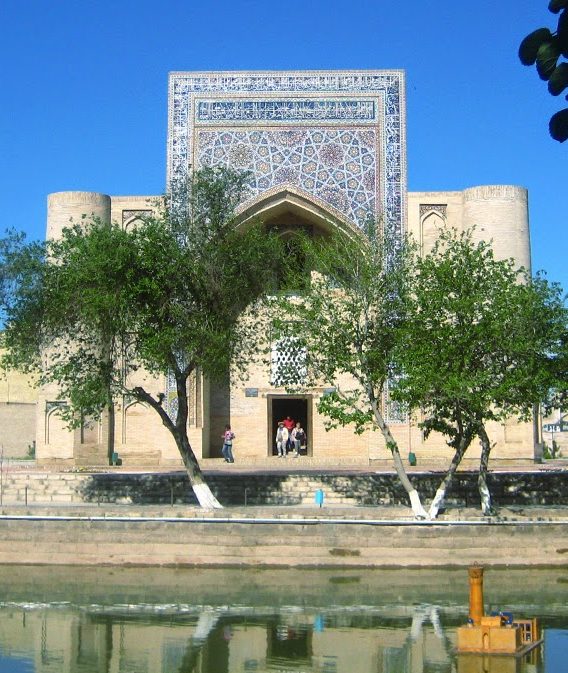

Lyabi-Hauz Complex

Lyabi-Hauz, a plaza built around a pool in 1620, is the most peaceful and interesting spot in town – shaded by mulberry trees as old as the pool. The old tea-sipping, chessboard-clutching Uzbek men who once inhabited this corner of town has been moved on by local entrepreneurs bent on cashing in on the tourist trade.

Chor Minor

Photogenic little Chor Minor, in a maze of alleys between Pushkin and Hoja Nurabad, bears more relation to Indian styles than to anything Bukharan. This was the gatehouse of a long-gone madrassa built in 1807. The name means ‘Four Minarets’ in Tajik, although they aren’t strictly speaking minarets rather decorative towers.

Sitorai Mokhi Hosa Summer Palace

For a look at the kitsch lifestyle of the last emir, Alim Khan, go out to his summer palace, Sitorai Mohi Hosa (Star-and-Moon Garden). The three-building compound was a joint effort for Alim Khan by Russian architects (outside) and local artisans (inside), and no punches were pulled in showing off both the finest and the gaudiest aspects of both styles. A 50-watt Russian generator provided the first electricity the emirate had ever seen.

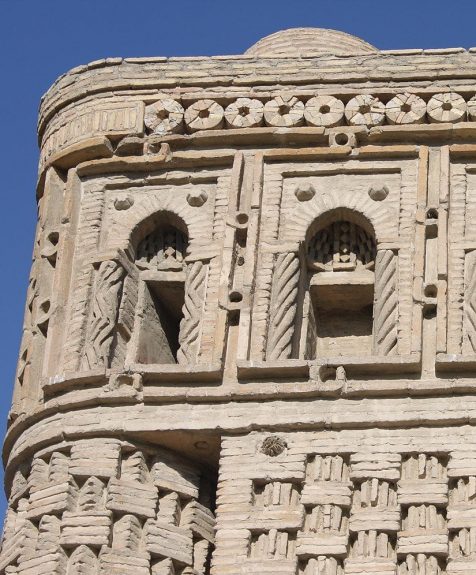

Ismail Samani Mausoleum

This mausoleum in Samani Park, completed in 905, is the town’s oldest Muslim monument and probably its sturdiest architecturally. Built for Ismail Samani (the Samanid dynasty’s founder), his father and grandson, its intricate baked terracotta brickwork – which gradually changes ‘personality’ through the day as the shadows shift – disguises walls almost 2m thick, helping it survive without restoration (except for the spiked dome) for 11 centuries.

Covered Bazaars

From Shaybanid times, the area west and north of Lyabi-Hauz was a vast warren of market lanes, arcades, and crossroad mini bazaars whose multi-domed roofs were designed to draw in cool air. Three remaining domed bazaars, heavily renovated in Soviet times, were among dozens of specialized bazaars in the town – domes: Taki Sarrafon (moneychangers), Taki-Telpak Furushon (cap makers), and Taki-Zargaron (jewelers). Here you could find different goods for sale, from handmade little crafts to silk carpets.

Gijduvan Museum of Ceramics

Gijduvan Museum of ceramics, in which the hereditary master of ceramics – Abdullo Narzullaev work with his family and pupils. The museum complex includes an exhibition hall, a ceramic workshop, and a house, built in a traditional manner. In the Museum of ceramics, you may get information regarding schools of ceramics in Central Asia and get acquainted with samples of pottery, representing several regions of Central Asia. In the ceramic workshop visitors may watch the real process of traditional ceramic utensils manufacture: manual moldings on potter’s wheels, painting, antique way of glaze preparation by means of a mill, which is rotated by a burro, and, at last, the roasting that is executed in traditional furnaces – “khumdons”. Visitors may also participate in this process, if interested.

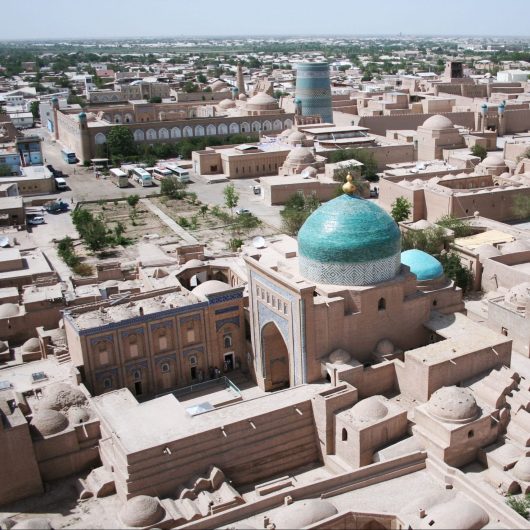

KHIVA

Khiva’s name, redolent of slave caravans, barbaric cruelty, terrible desert journeys, and steppes infested with wild tribesmen struck fear into all but the boldest 19th-century hearts. Nowadays it’s a friendly and welcoming Silk Road old town that’s very well set up for tourism and a mere 35km southwest of the major transport hub of Urgench.

The historic heart of Khiva has been so well preserved that it’s often criticized as lifeless – a “museum city”. To walk through the walls and catch that first glimpse of the fabled Ichon-Qala (inner walled city) in all its monotoned, mud-walled glory is like stepping into another era.

Itchan Kala - Inner City

Itchan Kala is the inner town (protected by brick walls some 10 m high) of the old Khiva oasis, which was the last resting place of caravans before crossing the desert to Iran. Although a few very old monuments still remain, it is a coherent and well-preserved example of the Muslim architecture of Central Asia.

Tosh-hovli Palace

This palace, which means ‘Stone House’, contains Khiva’s most sumptuous interior decoration, including ceramic tiles, carved stone and wood, and ghanch. Built by Allakuli Khan between 1832 and 1841 as a more splendid alternative to the Kuhna Ark, it’s said to have more than 150 rooms off nine courtyards, with high ceilings designed to catch any breeze.

Kalta Minor Minaret

Just south of the Kuhna Ark stands the fat, turquoise-tiled Kalta Minor Minaret. This unfinished minaret was begun in 1851 by Mohammed Amin Khan, who according to legend wanted to build a minaret so high he could see all the way to Bukhara. Unfortunately, the khan dropped dead in 1855 and it was never finished, leaving the beautifully tiled structure looking distinctly unusual and rather stumpy. It’s currently not possible to climb the structure.

Islom-Hoja Medressa & Minaret

Islom-Hoja Medressa and minaret – Khiva’s newest Islamic monuments, both built in 1910. You can climb the minaret. With bands of turquoise and red tiling, it looks rather like an uncommonly lovely lighthouse. At 57m tall, it’s Uzbekistan’s highest minaret.

Pahlavon Mahmud Mausoleum

This revered mausoleum, with its sublime courtyard and stately tilework, is one of the town’s most beautiful spots. Pahlavon Mahmud was a poet, philosopher and legendary wrestler who became Khiva’s patron saint. His 1326 tomb was rebuilt in the 19th century and then requisitioned in 1913 by the khan of the day as the family mausoleum.

Juma Mosque

The large Juma Mosque is interesting for the 218 wooden columns supporting its roof – a concept thought to be derived from ancient Arabian mosques. Six or seven of the columns date from the original 10th-century mosque, though the present building dates from the 18th century. From inside, you can climb the very dark stairway up to the 47m Juma Minaret.

TERMEZ

The last stop in Uzbekistan on the way to Afghanistan, Termez is a colourful border town with an edgy, Wild West feel. While the present day city bears few traces of its colorful cosmopolitan history, the surrounding area is full of archaeological finds, many of which come together in Termez’s excellent archeological museum.

Founded on the crossroad of caravan paths of the Great Silk Road, old Termez for centuries had been one of the leading towns of the Bactrian kingdom and Kushan Empire. Today Termez is a modern town and the center of the Surhandarya region.

Fayaztepa

The expansion of Buddhism was the reason of erection of the various types of Buddhist cultural constructions – underground and overhead, Fayaztepa is overhead temple – sangarama, where the central part formed the yard, surrounded by the gallery, decorated with valuable paintings. Small mortar was a part of the complex, located in the outsides of the temple in the wide yard, once surrounded by the walls on the small podium. The diameter of the mortar is 3 m. The exact date of the monument gives the rich numismatic material – I – IV centuries A.D.

Karatepa

Buddhist temple complex of Karatepa erected in the epoch of Kushan to the northwest outskirts of Ancient Termiz in the I-IV centuries B.C. Characteristic features of Karatepa concludes that majority of temple complexes were included both as overhead and cave constructions. The overhead part consists of open yard, by the perimeter of the located ayvan gallery. In the one part of the facade were situated the passageways, linked the overhead part with the cave. The overhead temple with big mortar has occupied the northern part of Karatepa.

Zurmala Stupa (Mortar)

Buddhist monument of Zurmala – rises up to the northeast from the fortress walls of Kushan Termez. Once here, in the suburb zone, were seemingly the whole complexes of Buddhist constructions, but at the Medieval centuries, this territory was occupied by the fields. Just the main construction – huge mortar, lacking in its facing transmitted the centuries. At present it only the unformed massif, however, excavations showed that the building had the rectangular pedestal, where was erected cylindrical shaped tower monolith with dome shaped coronation. The mortar of Zurmala – the biggest mortar among the known mortars of Central Asia, dated to I – II centuries A.D.

Kampyrtepa or Alexandria Oxiana

Kampirtepa is one of the unique ancient sites of the ancient settlement of Central Asia (III-I centuries B.C.). It discovered during archeological reconnaissance in Оks valley in 1972. Originally, it has been established as a fortress, located at the crossing through Оks by the caravan way from Baktria to Sogd. Kampirtepa consists of strengthened and not strengthened parts. As a result of archeological researches is established, that Kampirtepa was known in the history of the antiquity of Greek ferry. Archeological excavations except for set monetary treasures revealed the monuments of four writings – Greek, Bactrian, Brahma, and an unknown letter. In 2019 in Uzbekistan Kampyrtepa received the name of Alexandria Oxiana.

Archaeological Museum

Unveiled in 2001, the museum is a treasure trove of artifacts collected from the many ravaged civilizations that pepper the Surkhandarya province. The highlight would have to be the collection of 3rd- to 4th-century Buddhist artifacts. The museum also has an excellent model of Surkhandarya that depicts the area’s most important archaeological sights.

Qirq-Qiz (Kyrk-Kyz) Complex

Building of Qirq-Qiz means «Forty maidens», a national rumor connects with a legend widely widespread in Central Asia on the girls-amazons living in the strengthened castle. But in fact, the remains of the unique building is looks more like a Caravanserai or Hotel, where everyone who has money could stay and recover.

Dalverzintepa

In the 1st century B.C.E. Dalverzin Tepa, originally a small Greco-Bactrian fortified place, developed laterally into an extensive town surrounded by a fortification wall. It was in the Kushan period (1st-3rd centuries C.E.) that the town experienced its most active period of urban and defensive construction; the Greco-Bactrian nucleus was rebuilt as a citadel, and the fortification walls became almost twice as thick. In the 6th and 7th centuries, there was a smaller settlement on the site of the former citadel, but after the Muslim conquest in the early 8th century, Dalverzintepa was completely abandoned.

Sulton-Saodat Complex

Sulton-Saodat – the large architectural ensemble, is located in the territory, that has been developed after Mongolian Termiz. Sulton-Saodat is a group occurring at different times family tombs Termizian Seyidov and cult buildings, which represent original and complete ensemble. Its initial base is made in the southwest part. It includes two mausoleums, which are connected by a deep arch. Research showed structures of the lump sum are dated the XI century.

SHAKHRISABZ

Shakhrisabz is Timur’s hometown, and once upon a time it probably put Samarkand itself in the shade. Timur was born on 9 April 1336 into the Barlas clan of local aristocrats, at the village of Hoja Ilghar, 13km to the south. Ancient even then, Shakhrisabz (called Kesh at the time) was a kind of family seat. As he rose to power, Timur gave it its present name (Tajik for ‘Green Town’) and turned it into an extended family monument. Most of its current attractions were built here by Timur (including a tomb intended for himself) or his grandson Ulugbek.

Amir Temur Statue

A new statue of Amir Timur stands in what was the palace centre. It’s not uncommon to see 10 weddings at a time posing here for photos at weekends, creating quite a mob scene.

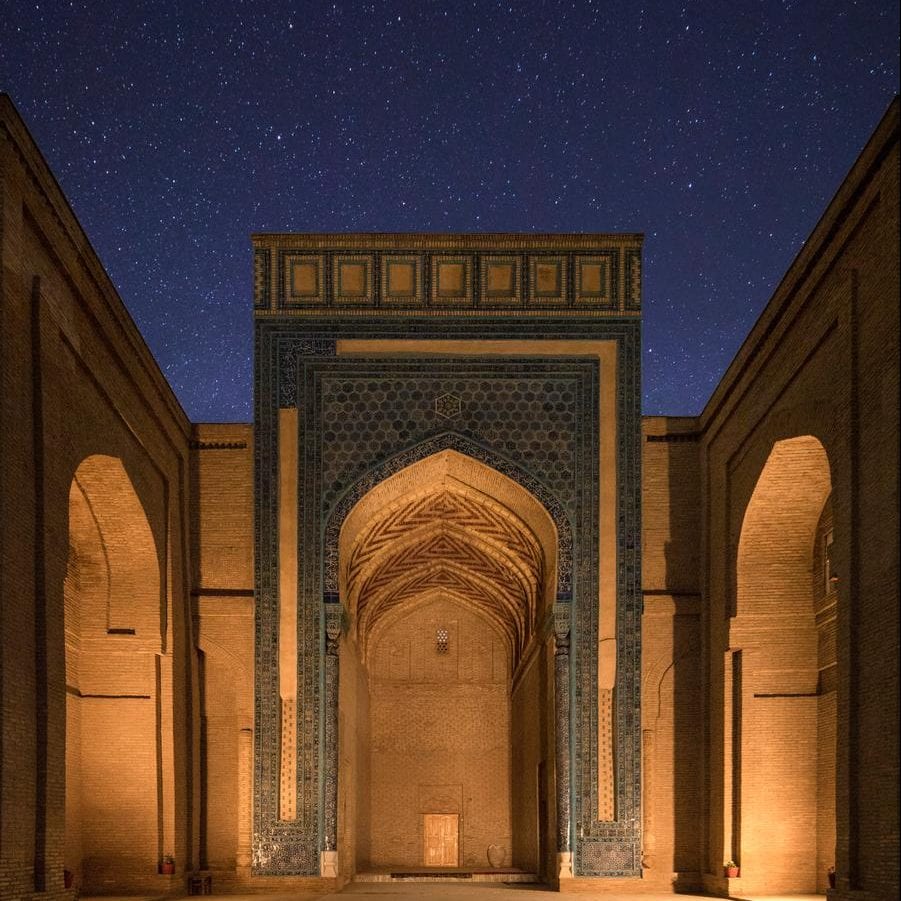

Ak-Saray Palace

Ak-Saray was probably Timur’s most ambitious project – work began in 1380 and took some 24 years to complete. Its creation followed a successful campaign in Khorezm and the ‘import’ of many of its finest artisans. It’s well worth climbing to the top of the pishtak to truly appreciate its height and imagine what the rest of the palace was like, in size and glory. The arch was a staggering 22.5m wide, and collapsed 200 years ago. There’s actually nothing left of it except bits of the gigantic, 38m-high pishtak, covered with gorgeous, unrestored filigree-like mosaics.

Dorut Tilyovat

Mausoleum

Dorut Tilyovat, the original burial complex of Timur’s forebears. Under the dome on the left is the Mausoleum of Sheikh Shamseddin Kulyal, spiritual tutor to Timur and his father, Amir Taragay (who might also be buried here). The mausoleum was completed by Timur in 1374.

Dorus Saodat

Dorus Saodat or Seat of Power and Might, which Timur finished in 1392 and which may have overshadowed even the Ak-Saray Palace. The main survivor is the tall, crumbling Tomb of Jehangir, Timur’s eldest and favourite son, who died at 22. It’s also the resting place for another son, Umar Sheikh (Timur’s other sons are with him at Gur-e-Amir in Samarkand).

Fergana Valley

The first thought many visitors have on arrival in the Fergana Valley is, ‘Where’s the valley?’ From this broad (22,000 sq km), flat bowl, the surrounding mountain ranges (Tian Shan to the north and the Pamir Alay to the south) seem to stand back at enormous distances – when you can see them, that is. More often these spectacular peaks are shrouded in a layer of smog, produced by what is both Uzbekistan’s most populous and its most industrial region. Fergana is also the country’s fruit and cotton basket. Drained by the upper Syrdarya, the Fergana Valley is one big oasis, with some of the finest soil and climate in Central Asia.

Already by the 2nd century BC the Greeks, Persians and Chinese found a prosperous kingdom based on farming, with some 70 towns and villages. It is also the centre of Central Asian pottery and silk production.

Fergana

Tree-lined avenues and pastel-plastered tsarist buildings give Fergana the feel of a mini-Tashkent. Throw in the best services and accommodation in the region, plus a central location, and you have the most obvious base from which to explore the rest of the valley. Fergana is the valley’s least ancient and least Uzbek city. It began in 1877 as New Margilon, a colonial annexe to nearby Margilon. It became Fergana in the 1920s.

Rishtan

This town is famous for the ubiquitous cobalt and green pottery fashioned from its fine clay. About 90% of the ceramics you see in souvenir stores across Uzbekistan originates here – most of it handmade. Some one thousand potters make a living from the legendary local loam, which is so pure that it requires no additives (besides water) before being chucked on the wheel. Of those thousand potters only a handful are considered true masters who still use traditional techniques. Among them is Rustam Usmanov, he runs the Rishton Ceramic Museum.

Yodgorlik Silk Factory

Margilon’s main attraction is this fascinating factory, which can be explored on a tour where you’ll witness traditional methods of silk production from steaming and unravelling the cocoons to the weaving of the dazzling khanatlas (handwoven silk, patterned on one side) fabrics for which Margilon is famous. Here you can buy silk by the metre, here is also premade clothing, carpets and embroidered items for sale.

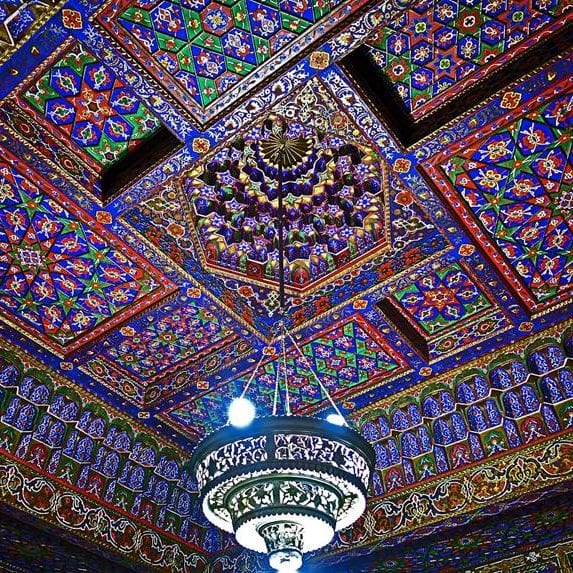

Kokand Khan’s Palace

The Khan’s Palace, with seven courtyards and 114 rooms, was built in 1873, though its dazzling tiled exterior makes it look so perfect that you’d be forgiven for thinking it was as new as the modern park that surrounds it. Just three years after its completion, the tsar’s troops arrived, blew up its fortifications and abolished the khan’s job. The Khan in question was Khudayar Khan, a cruel ruler who had previously been chummy with the Russians.

Ahsiket

Ancient Settlement

A site of ancient settlement Ahsiket located on the right branch of Sirdarya River in Turakargan district of Namangan region. Its area occupies the territory of more than 25 hectares. The city founded in III - II centuries B.C. and functioned up to 1219 A.D. It has been completely destroyed by Mongolian forces. The city structure consisted of the citadel, Shakhristan - the city itself and rabad - suburb of the city. All three parts of the city have been enclosed by the fortification.

Kuba

Kuba is an early medieval walled town in the center of the modern city of Kuva where at the north of the shahristan outside the walls was located a Buddhist sanctuary including clay sculptures of horses and big statues of Buddha and the Buddhist pantheon (VII-VIII AD). Hui Chao, who crossed the valley in 724, reported that there were no followers of Buddhism in the region. May be, by the time, the Arab invasion already destroyed the Kuba sanctuary.

KARAKALPAKSTAN

If you’re attracted to desolation, you’ll love the Republic of Karakalpakstan. The Karakalpaks, are a formerly nomadic and fishing people. The destruction of the Aral Sea has rendered Karakalpakstan one of Uzbekistan’s most depressed regions. The capital, Nukus, feels half deserted, and a drive into outlying areas reveals a region of dying towns and blighted landscapes.

However, as the gateway to the fast-disappearing Aral Sea and home to the remarkable Savitsky Museum – one of the best collections of Soviet art in the world – there is actually a reason to come here, other than taking in the general sense of hopelessness and desolation.

The Savitsky Museum

Museum houses one of the most remarkable art collections in the former Soviet Union. The museum owns some 90,000 artefacts and pieces of art – including more than 15,000 paintings – only a fraction of which are actually on display. About half of the paintings were brought here in Soviet times by renegade artist and ethnographer Igor Savitsky, who managed to work within the system to preserve an entire generation of avant-garde work that was proscribed and destroyed elsewhere in the country for not conforming to the socialist realism of the times.

Moynaq

Moynaq, 210km north of Nukus, encapsulates more visibly than anywhere else the absurd tragedy of the Aral Sea. Once one of the sea’s two major fishing ports, it now stands almost 200km from the water. What remains of Moynaq’s fishing fleet lies rusting on the sand in the former seabed.

Ayaz Kala Fortress

The towering mud-brick walls of the three fortresses at Ayaz Kala, rise dramatically from the surrounding plains. They were built on the edge of the Kizilkum Desert at different points between the 4 century B.C. and the 7 century A.D. as a means of protection from nomad raids. Within the forts are the remains of palaces and traces of the local agricultural population have been found in the surrounding areas. Abandoned for 1,300 years, the fortresses were rediscovered in the 1940s by the archaeologist S.P. Tolstov.

Toprak Kala Fortress

The Royal Residence of Toprak Kala are extremely significant historical and architectural structures created during the 2nd and 12th centuries A.D., respectively. Seemingly formed straight from the earth, the façades of the castles and fortifications have softened through centuries of exposure to wind and other natural elements. Today, cotton cultivation has salinized the soil surrounding the structures, eating away at the foundations and compounding the deterioration left by time and the environment.

Tashkent

Sprawling Tashkent is Central Asia’s hub and the place where everything in Uzbekistan happens. It’s one part newly built national capital, thick with the institutions of power, one part leafy Soviet city, and yet another part sleepy Uzbek town, where traditionally clad farmers cart their wares through a maze of mud-walled houses to the grinding crowds of the bazaar. Tashkent’s earliest incarnation might have been as the settlement of Ming-Uruk in the 2nd or 1st century BC. By the time the Arabs took it in AD 751 it was a major caravan crossroads. It was given the name Toshkent, ‘City of Stone’ in Turkic, in about the 11th century.

Museum of Applied Arts

The Museum of Applied Arts occupies an exquisite house full of bright ghanch and carved wood. It was built in the 1930s, at the height of the Soviet period, but nonetheless serves as a sneak preview of the older architectural highlights lurking in Bukhara and Samarkand. The ceramic and textile exhibits here, are a fine way to bone up on the regional decorative styles of Uzbekistan.

Sate History

Museum of Uzbekistan

The History Museum is a must-stop for anyone looking for a primer on the history of Turkestan from ancient times to the present. The 2nd floor has Zoroastrian and Buddhist artefacts, including several 1st- to 4th-century Buddhas and Buddha fragments from the Fayoz-Tepe area near Termiz.

Khast Imom Complex

The official religious centre of the republic, located 2km north of the Circus, is also definitely one of the best places to see ‘old Tashkent’. A big renovation in recent years has left the complex looking better than ever. The Hazroti Imom Friday mosque, flanked by two 54m minarets, is a recent construction. Behind it is the sprawling Khast Imom Square, Barak Khan Madrassah, The Muslim Board of Uzbekistan and the primary attraction of the Khast Imom square, the library museum, which houses the 7th-century Osman Quran (Uthman Quran), said to be the world’s oldest.

Alisher Navoi Theatre

Tashkent's main opera and ballet theatre is worth a visit as much for its impressive interior as its fine opera and ballet performances. Verdi and Puccini are standards, or be bold and try a Soviet Uzbek opera by Mukhtar Ashrafi. The ticket office is hidden in one of the exterior pillars. Designed by Alexey Shchusev, the building of the theater was built in 1942-1947 and was opened to the public in November, 1947, celebrating the 500th anniversary of the birth of Alisher Navoi. The theater has a capacity of 1,400 spectators, the main stage is 540 square meters big.

Chorsu Bazaar

Tashkent’s most famous farmers market, topped by a giant green dome, is a delightful slice of city life spilling into the streets off Old Town’s southern edge. If it grows and it’s edible, it’s here. There are acres of spices arranged in brightly coloured mountains; Volkswagen-sized sacks of grain; entire sheds dedicated to candy, dairy products and bread; interminable rows of freshly slaughtered livestock; and of course scores of pomegranates, melons, persimmons, tomatoes and whatever fruits are in season. Souvenir hunters will find kurpacha (colourful sitting mattresses), skull caps, chapan (traditional cloaks) and knives here.

Tashkent Metro

The Tashkent Metro is the rapid transit system serving the city of Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan. It was the seventh metro to be built in the former USSR, opening in 1977, and is one of only two subway systems currently operating in Central Asia (the other one being the Almaty Metro). Its stations are among the most ornate in the world, and unlike most ex-Soviet metros, the system is shallow, similar to the Minsk Metro.