Desolate lands

Rising between the Caspian and Aral seas and stretching across Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, the Ustyurt plateau is an ultra-remote expanse of scorched clay-desert valleys that surge into rust-red pinnacles and mesas. This otherworldly 200,000 sq km expanse is roughly the size of England and Scotland combined, but with fewer than 13cm of annual rainfall and extreme seasonal temperatures that swing between 40°C and −40°C, the arid region is only home to a few sparsely populated semi-nomadic tribes.

Yet, a deeper look at this seemingly desolate land reveals a series of mysterious, ancient fortifications – suggesting that people have survived and even thrived in this harsh climate against all odds.

Ancient waters

Weather-worn limestone cliffs, locally known as chink, characterise the Ustyurt and can climb more than 200m high. Many stretches overlook large salt pans, which form shallow, ephemeral lakes that appear briefly each year during the rare winter and summer rains.

Until 21 million years ago, the Ustyurt was part of the Tethys Sea that is believed to have formed the Black, Aral and Caspian seas. Poking around the plateau’s salt-encrusted, chalk-white slopes, it’s easy to still find shark teeth, ammonite shells, belemnite and countless other fossilised marine organisms that once swam through this bone-dry landscape.

A tough environment

The few people who visit the plateau each year generally travel to Kazakhstan’s Ustyurt Nature Reserve, located in the southern Mangystau region. Established in 1984, it is 1.5 times the size of Greater London and home to nearly 300 different types of flora and fauna, such as Brandt’s hedgehogs, wild boar, marbled polecats and the houbara bustard bird. One of the rarest inhabitants of the protected area is a single Persian leopard, first spotted in 2018, and one of only three ever recorded in Kazakhstan.

Mysterious structures

Dotted around the edge of the Ustyurt’s escarpments are a series of ancient stone-and-dirt structures known as “desert kites”. The term originates from French and British military pilots who first spotted the curious complexes in the 1920s while flying over the Middle East.

Characterised by two or more rows of long arrow-like stone lines that converge in an enclosed circular pit, the kites have attracted considerable archaeological interest for more than 35 years. But according to The desert kites of the Ustyurt Plateau report published in Quaternary International, “their size and the almost total absence of archaeological artefacts render any conclusions on their study very approximate.”

In recent years, a French research project called Global Kites has compiled more than 4,600 satellite images of desert kites scattered across the Levant, Saudi Arabia, Armenia, Yemen and the Kazakh and Uzbek sections of the Ustyurt, and it is believed that more than 5,800 of these mysterious structures exist around the world.

Ancient ingenuity

Over the years, archaeologists have posited that these puzzling funnel-like structures may have served as living quarters, domestic animal fences or cultic sites. Russian archaeologist-ethnographer Sergey Tolstov was the first to discover the Ustyurt’s kites in 1952. Radiocarbon dating suggests that some could be more than 2,000 years old, and, remarkably, a number may have been in use as hunting pens until the mid-20th Century, according to ethnographical accounts.

Today, the most widely accepted theory is that these cryptic artefacts were designed for trapping the critically endangered saiga antelope that once swarmed the Central Asian steppes during their late summer migration, in addition to other ungulates such as wild Asian donkeys, Urial sheep and Jairan antelope. According to researchers, the ancestors of the few nomadic pastoralists who still roam the plateau today likely worked in large teams to funnel the migrating animals into these narrow, V-shaped enclosures before killing them for food.

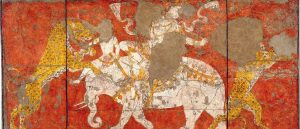

Shifting rulers

For millennia, this rugged corner of Central Asia has seen numerous civilisations come and go. According to Professor Alison Betts, a Scottish archaeologist specialising in the Silk Roads and Near East nomadic peoples, the region was a favourite winter ground for nomads from the Iron Age into the early 20th Century. But as rulers came and went, scholars think one of the few constants on the plateau for the last 2,000 years has been the desert kites.

The Amu Darya delta, which empties into the Aral Sea and adjoins the eastern extent of the Ustyurt, supported numerous tribes and civilisations. The region’s Bronze Age hunter-gatherers were absorbed into the First Persian Empire in the 7th to the 5th centuries BCE and later into the Mongol Empire during the Middle Ages. As Betts points out, the plateau’s fortresses were often sacked and raided over the centuries, but the hide, meat and horns of the desert’s kite-captured game formed an important part of the shifting empires’ economies and were traded elsewhere in Eurasia through the Silk Road network.

Looking forward

In recent years, scientists have sought to expand Kazakhstan’s Ustyurt Nature Reserve into Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. According to Dr Rémy Crassard from the French National Centre for Scientific Research and the Global Kites’ project leader, “The kites’ makers required social cooperation and ecological awareness to design, create and use these giant traps. Preserving the area allows us to continue our archaeological research, learn more about the region’s ecology and [understand] how past and present humans interact with the environment.”

Scientists like Crassard hope that through multilateral collaboration and unified land-management policies, expanding the reserve could lead to future Unesco World Heritage status, which would provide funding for long-term protection from poaching and non-sustainable development.

Copyrights: BBC, article by Matthew Traver (2020/09/07)

Original source: here

Credits: kiwisoul, Yerbolat Shadrakhov, Riverwill – Getty Images and Matthew Traver